The biggest challenge with turning Just Mercy into a feature film is that the story is too perfect. Walter McMillian, a black man in 1980s Alabama, infuriates a white community by having a relationship with a white woman and when police aren’t able to solve an unrelated murder he is scapegoated, arrested, convicted, and sentenced to death by corrupt prosecutors, a bias judge, and a jury chosen by racially discriminatory means. All hope looks to be lost until Bryan Stevenson, a young, idealistic, Harvard lawyer, finds his case and works it till McMillian is free. You could not do a better job encapsulating all that is wrong with the US criminal justice system in one case if you tried, no doubt Stevenson chose this case to be the skeleton of his legal memoir for that exact reason, but the feature film adaptation begs the question: When dealing with an issue so important and pertinent as the US criminal justice system, should a based-on-a-true-story film be willing to sacrifice factual accuracy to bolster its narrative strength?

Both in the film and in real life Stevenson is essentially a legal superhero. After graduating from Harvard Law he worked for the Southern Center for Human Rights before founding the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) which provides legal service to those on death row. When he was given a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship in 1995 he took the cash prize and put it all towards funding EJI’s work (of course). He has argued and won cases in front of the Supreme Court, worked to develop the National Memorial for Peace and Justice (a memorial for victims of lynching in the US), and has been a crusader for history education in the US. The world is a better, more just place because of the work that Bryan Stevenson has done. But as a character in a narrative film – and I realize how awful what I’m about to say sounds because I truly have endless admiration for Bryan Stevenson – but he lacks depth.

Michael B. Jordan does an excellent job conveying his relentless will to fight injustice and the legal gravitas he brings to a courtroom, but because all we see is his altruistic fight for justice there seems to be an underlying human aspect missing from his character. Is Stevenson truly motivated solely by altruism and the fight for justice or is there any self-interest hidden in there that we didn’t get to see? Does he want fame? Does he want a family? Does he want to go down in history books as a crusader for justice so in 100 years when children in America open their textbooks to the Mass Incarceration chapter they will see his name on the right side of history? I don’t think any of these desires would be bad or undermine his work in any way, in fact I think it’s healthy to acknowledge our own self-centered goals and how they impact our work in good and bad ways. In the book Just Mercy this feels like less of an issue as the book is more focused on the cases and the legal system, but in the film when you have Michael B. Jordan up there on the big screen it’s hard not to wonder, when he closes his law books and rests his head for the night, what is he thinking about?

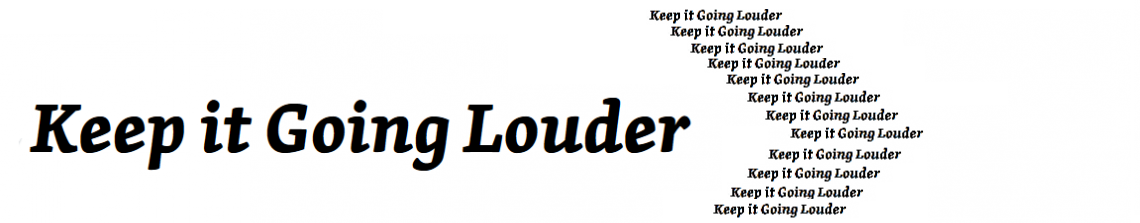

Michael B. Jordan (left) as Bryan Stevenson (right)

The most full characters in the film are all of the men imprisoned; some innocent, some mentally ill, virtually all subjected to punishment that borders on torture, and when we meet them we get to see their whole stories, good and the bad, the richness of their imperfect lives. However, due to the nature of their imprisonment, these characters have no ability to change even their own stories and for the most part they can only watch as their lawyers and the state of Alabama lock horns to determine their future.

Though we briefly meet some of the authority figures who are responsible for McMillian’s imprisonment, we never get a good sense of who they are either. No doubt some of them are power-hungry or racist or both but I suspect that most of the police, lawyers, and judges who had a hand in McMillian’s case thought they were doing the right thing when they arrested, tried, and convicted him. How did these people get it so wrong? Was it pure bigotry? Bias created by subconscious prejudice? Did they know that this man was innocent but think that the social pressure was so high in this case that they would be able to do more good and preserve more justice for others in the future if they allowed McMillian to be steamrolled? We will likely never know the motivations of the real individuals, I doubt they would be welcoming to an in-depth and emotionally honest interview about their actions in the case, but the film could have benefited from trying to investigate who some of these authority figures were and why they were so adamant to execute a clearly innocent man. In keeping the focus on Stevenson and McMillian we could only see them battle against a collage of racist stock characters rather than complex human beings.

One month after Just Mercy’s US release, another film came out that is the perfect yin to Just Mercy’s yang, the excellent and powerful Clemency. Written and directed by Chinonye Chukwu (a rising star, if you will, Clemency won the U.S. Dramatic Grand Jury Prize at Sundance Film Festival and she’s slated to direct a film adaptation of Black Panther Party member Elaine Brown’s memoir), Clemency focused on the opposite side of death row. The film follows Prison Warden Bernadine Williams, played by Alfre Woodard, as she struggles with the psychological impact of overseeing executions conducted at her prison. The film manages to make a bold statement about the morality of the death penalty and the flaws in the US criminal justice system while also exploring the life of a person who is driving the system’s oppressive forces. Being a work of fiction and narrow in scope allowed Clemency to dig deep into the psyche of Warden Williams without sacrificing any other aspects of the film; Just Mercy might not have been able to go as deep but would have benefited from at least a cursory look at the inner lives of those who are wielding oppressive force.

Aside from my narrative squabbles, the film is constructed with the skill and touch you would expect from the all-star team. Jordan and Foxx could each have easily given a more Oscar-baity performance with a whole lot of yelling and s e r i o u s a c t i n g but they wisely took a more nuanced route and let their physicality give power to their performance, especially as they are framed by the cramped, cloistered prison and the wide-open nature of rural Alabama.

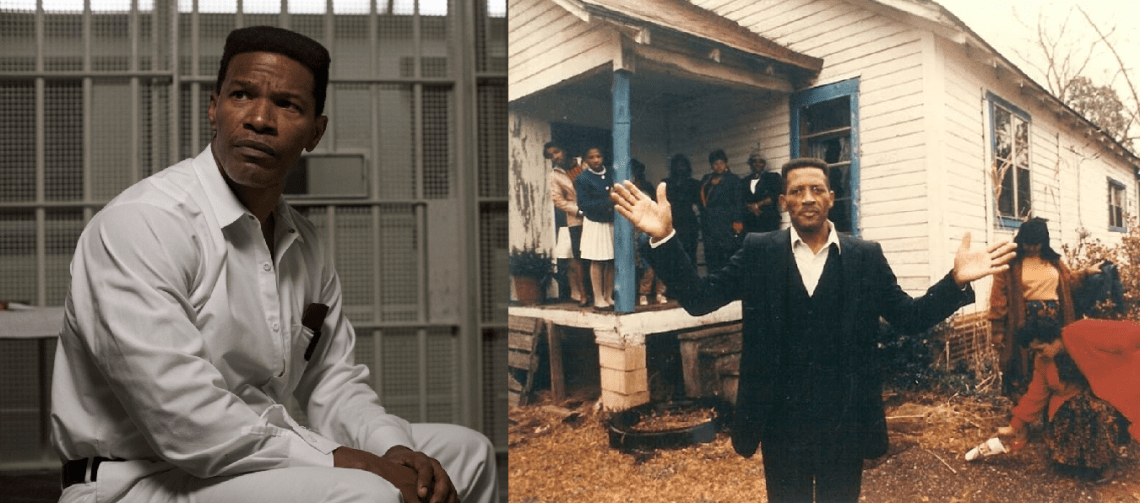

Jamie Foxx (left) as Walter “Johnny D” McMillian (right)

Destin Daniel Cretton showed his growing mastery as a director with the tight screenplay (co-wrote with Andrew Lanham), efficient pacing, and some incredibly powerful individual scenes. The courtroom scenes are whip-sharp and the execution of Herbert Richardson is especially haunting, as Richardson is strapped down and put to death the prison mugs clank against the prison bars into a crescendo of community, freedom, life, and loss. However, like in his last film The Glass Castle, Cretton is held back by the trade-offs of sacrificing narrative power to maintain factual integrity.

I have long had a special place in my heart for Cretton. Back in 2013 he burst onto the scene with Short Term 12, one of my all time favorite movies and in my humble opinion the 6th best film of the 2010s. Based on his personal experiences working at a group home for teenagers he was able to capture all of the joy and pain of the people who inhabit that world in a way that felt fresh and alive, empathetic without being pandering. He no doubt was able to draw from what he saw in real life to inform the film but not being restrained by facts to stick to he could craft a compelling narrative while maintaining the emotional impact. The Glass Castle and Just Mercy display all of the same care and skill but the stories aren’t malleable in the same way and some power is lost in the transition from memoir to feature film.

Quick digression on 2013, wow what a year for indie films. In addition to Short Term 12 you had Ryan Coogler’s powerful debit Fruitvale Station, Lake Bell’s hilarious and charming In a World…, Harmony Korine’s batshit-insane Spring Breakers, and Greta Gerwig & Noah Baumbach’s sublime Frances Ha. I definitely thought that Cretton-Coogler-Bell were going to be a powerhouse young directing trio that was going to light the movie world on fire…I hit it on the nose with Coogler (Fruitvale Station → Creed → Black Panther → global dominance), Cretton is still right on the line between budding talent and indie auteur, and Bell has stuck mostly to acting in the years since which is kind of a disappointment. She directed one film since, I Do…Until I Don’t; I haven’t seen it but word on the street is it’s a stinker. Maybe she’ll pick back up in the 2020s. Feels like 2013 is ripe for a retrospective, maybe another time.

One last thing on Cretton, he’s slated to direct Marvel’s Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings which should be incredibly interesting. He’ll follow in the footsteps of many indie darling directors who make the leap from small-scale films to giant blockbusters and I’m very excited and maybe a little nervous to see how it turns out. Unclear if Brie Larson will make an appearance, she’s been in all three of Cretton’s major releases so far, gotta keep that actor-director streak going. She’s in the MCU as Captain Marvel so it’s certainly a possibility, does Shang-Chi ever interact with Captain Marvel? Maybe Captain Marvel can help him get one of the ten rings? Okay, enough of that, back to Just Mercy.

Destin Daniel Cretton (left) in deep though, perhaps about Shang-Chi (right) and how to get Brie Larson to make a cameo in his upcoming film.

Is the story of Just Mercy about success or failure? In the context of this one case, it’s clearly about success. A lawyer meets a man who is wrongfully imprisoned and set to be executed, works hard, fights the system, perseveres, and ultimately succeeds. McMilian is freed and cleared of any wrongdoing. However, when you take a step back, Just Mercy reads more as a story of colossal failure. A man was able to be convicted and sentenced to death with virtually zero evidence, it took one of our generations most talented and persistent lawyers years of work to get him free, and even after winning his freedom the man was permanently scarred by the brutal treatment he received in prison (McMillian developed dementia later in life, likely caused by trauma experienced in prison). Stevenson’s work to free McMillian is certainly a positive step, even more than in just his one case as hopefully others can use his work as a roadmap to free other individuals wrongfully imprisoned, but a system that requires lawyers of extreme talent to correct even it’s more egregious errors is no system that can bring about true justice.

The specific way in which the legal system failed Walter McMillian is noteworthy as well; the letter of the law seems to be appropriate in his case1, it was the people who were in charge of the system who were the source of the failure. Stevenson basically spent the whole appeal process forcing the state of Alabama to follow its own rules and only when they begrudgingly agreed was McMillian able to be free. In other cases Stevenson handled it was the rules that needed to be changed, such as the cases where children under the age of 18 were being sentenced to life imprisonment or to death (eventually these were both ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in Miller v. Alabama and Roper v. Simmons), but in the case of McMillian the rule of the legal system should have protected him. They did not. More than a failure of the legal system, McMilian’s case reflects a failure of society.

At every step the people in charge of the criminal justice system disobeyed the laws and Walter McMillian paid the price. The police made false statements and invented evidence to arrest him, the prosecutors asked for testimony that they knew to be false and withheld evidence they were legally required to share with the defense, and the judges allowed for a bias and unfair trail then refused to hold anyone who broke laws while prosecuting this case responsible for their crimes. It’s daunting to see how people can be so callous to the well-being of others, so quick to condemn a man to execution based on prejudice and blood-lust. Changing the rules of a legal system may take years of work but when it comes down to it, the change is really as simple as ink on parchment. Just Mercy shows that getting people steeped in the oppressive history of their past to enforce these new laws in a just and moral way is the true challenge to fixing our broken justice system.

—

1Some would argue that any law that permits for a death penalty is inherently flawed and immoral, and I generally tend to agree, but from what I understand this case wouldn’t have been drastically different in a legal sense if McMillan was facing life in prison as opposed to execution so I’m going to let that stand for now. In case you’re wondering…I do believe that there are crimes that if committed, being put to death would be a moral punishment for. I don’t want to get into conjuring up grisly examples but in the abstract I think the death penalty can be moral. However, in order for the death penalty to be implemented in a moral way I think the legal system would have to be able to guarantee that not a single innocent person would ever be put to death and there would have to be conclusive, unassailable evidence that any person condemned to death committed the crimes they were accused of. Since no legal system on this earth could ever make that guarantee and I believe it is far, far worse to put one single innocent person to death than to keep everyone who may be “deserving” of the death penalty in prison for life, I believe that no criminal justice system should have a death penalty.

Slam Zuckert is a municipal bureaucrat. He sees a lot of movies and reads a lot of books and sometimes writes about them. His favorite movie is There Will Be Blood, his favorite mathematician is Georg Cantor, and his least favorite mathematician is Leopold Kronecker.